Modal 3 Aonad 2

A-mach gu biadh

Eating out. Food and health.

Listening extracts for Aonad 2

Cultar

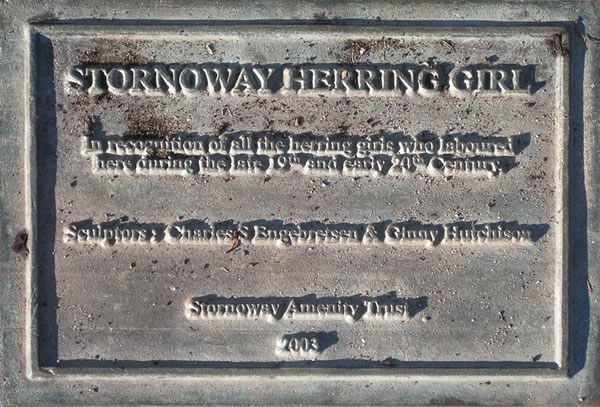

Clann-nighean an sgadain

Clann-nighean an sgadain (the herring girls) were the women who worked in the herring fishing industry in the late 1800s and early 1900s; gutting, salting and packing the catch as it was landed in all the major herring ports round Britain.

Around 1914, the herring industry was booming. Scotland was exporting around 2.5 million barrels of sgadan saillte (salt herring) a year, making its fishing industry the largest in Europe.

Stornoway was one of the largest herring ports in Britain at that time.

In 1914, 20% of the population of Lewis worked at the herring.

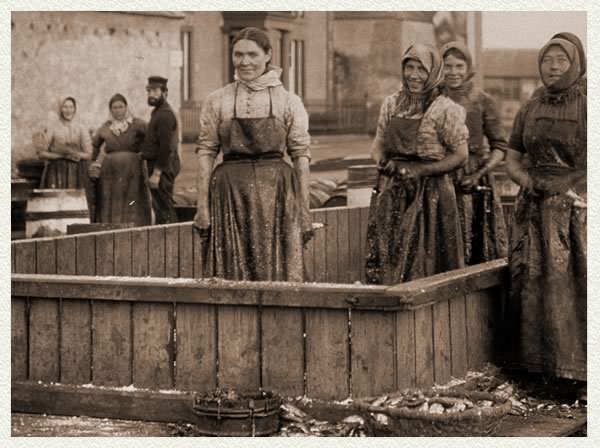

Three thousand of those were women – some as young as fifteen. It is said that of all the girls working as cutairean (gutters) around Britain, the women of Lewis were thought to be the best workers.

“nan tràillean aig ciùrairean cutach”

Before the season began each year, ciùrairean (curers) would choose a team of skilled cutairean they wanted to work for them.

These women would be given a down-payment called an àirleas to secure them for labour for the season.

The girls always worked in teams of three – two cutairean and a packer and it was the responsibility of those women paid an àirleas to recruit the other two members of her team.

A skilled team could gut and pack 21,000 herring during a ten hour shift.

“Thall ’s a-bhos air Galltachd ’s an Sasainn”

Each herring season, girls would ‘travel the herring’.

They would travel huge distances round the coast of Britain, following the migrating shoal.

This meant they were away from their homes and families for months at a time.

When they went away, each girl would take with her a few items of clothing and personal possessions, bedding and the crockery and cultlery she would need for meal times.

This would be carried in a ciste (a wooden chest). Whilst the women were away, they would live in basic little wooden shacks near the dock, sharing with up to five other girls.

“gaoth na mara geur air an craiceann”

Teams would be expected to be on hand the minute the fish was landed by the boats.

This sometimes meant long hours waiting around (unpaid) on the cold and blustery dockside.

To pass the time while they were waiting for the boats the women would chat, sing songs and knit.

When they were working, they would wear an oilskin apron and big rubber or leather boots to protect their clothes and feet.

A headscarf would prevent some of the fish scales and salt from getting into their hair and a woolen shawl kept out some of the cold.

Surprisingly, they didn’t have any gloves to protect their hands from the gutting knife and this often left them with painful cuts and wounds on their hands that were made worse by the frequent exposure to icy cold water and salt.

“na miaran cruinne, goirid a dhèanadh giullachd”

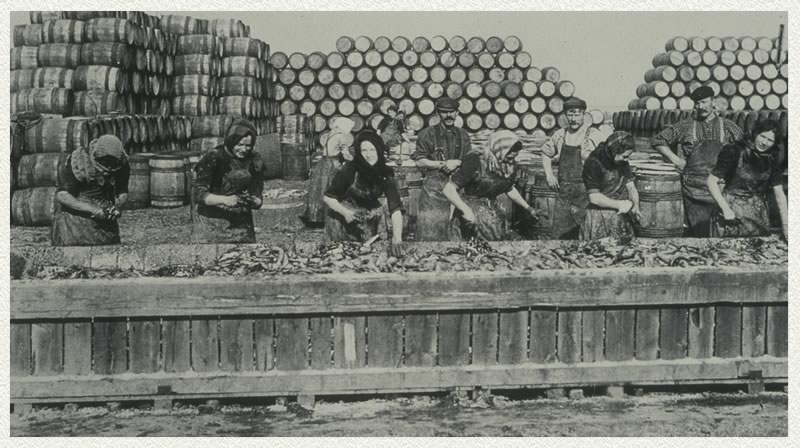

When the herring was landed, it was poured into a fàrlain (a big wooden trough) with water and plenty of rough salt.

The women would stand over this, poised with a cutag (a sharp gutting knife), ready to start work.

As they gutted, they would throw the fish intestines into a gut basket, and simultaneously assess the size and grading of each fish, throwing it into the appropriate basket behind them, ready for the packer.

The girls were so used to their work, they could almost do it blindfold. An average cutair could gut and sort around 40 herring a minute, but the most experienced ones could manage up to double that amount.

Because herring is an oily fish, it had to be cured with salt as quickly as possible to prevent it from rotting.

Apart from this, the salt had an additional benefit. It made the gutters’ job easier because the coarse salt made the fish less slippery to handle.

In an effort to protect their hands, the women wrapped cotton rags tightly around their fingers. But, working quickly with slippery fish and a razor sharp cutag meant that nasty cuts were sometimes inevitable.

Working elbow deep in wet salty fish meant that the smallest of nicks would be very painful and slow to heal, so they had to be extremely careful.

Not only were their hands uncomfortable, but if they were too damaged to work, they and their team would suffer loss of wages as a result.

“na mìltean bharaillean ud”

The tallest girl of each team would be assigned as the pacair (packer).

She had to be tall enough to bend over into the barrel and reach the bottom of it. The fish had to be packed in layers, tightly and very precisely – belly facing upwards.

The packers were supervised by cùbairean (coopers) who kept a watchful eye on how the work was done.

When a girl completed the first layer of fish in the bottom of the barrel, she would shout for the cùbair. If he was happy with the layer, she would then add a layer of coarse salt to cover the fish before beginning the next tier.

When a barrel was filled, this was called a’ chiad lìonadh (the first filling). It would then be rolled on its side, and left for about ten days or so, to allow the herring to settle.

After that, it was time for an t-ath lìonadh (the next filling). The picil (pickle/brine) was drained from the barrel and more fish added to it. The saved picil would then be poured back in.

An treas lìonadh (the third, and last, filling) finally filled the barrel to the brim. It would then be sealed and branded with the date and the packer’s identity number, ready for shipping.

“Bu shaillte an duais a thàrr iad”

There is little doubt the herring girls’ work was laborious and repetitive.

They worked long hours, six days a week, separated from their families for long periods of time and for poor pay.

Unlike many jobs today, the gutting team would be paid by the barrel, not by the hour.

The payment was split between each member of the team.

Therefore, the faster the girls worked the more wages they received. Teams in Stornoway in the 1930s were paid around one shilling per barrel. Girls in their first year at the herring were called cuibhlearan (coilers).

They were paid less than the more experienced girls.

But it didn’t take them long to learn their trade. By the time they had completed one season, they would be fully familiar with the work and able to earn as much as the others.

“An gàire mar chraiteachan salainn”

Hard as the work was, the herring girls were well-known for their good spirits, wit and humour. There was always plenty of fun and banter amongst them. They would often sing òrain obrach (working songs) together to pass the time and there was certainly no shortage of fun when they did get some time off.

A’ tilleadh Dhàchaigh

Families at home would very much look forward to the girls coming back from the herring.

Each girl would arrive home with her ciste full of presents of things that were expensive to buy and difficult to get in Lewis. Here two of the girls talk about what they would take home.

“Bhiodh sinn ri toirt Dhàchaigh tòrr phreusantan gu na càirdean ’s dh’fheumadh sinn sin – blobhsaichean brèagha a chitheadh sinn ann am bùth: h-abair gum biodh sinn spaideil an uair a thigeadh sinn Dhàchaigh. Bhiodh sinn ri toirt Dhàchaigh tòrr shoithichean, ’s bha iad cho saor. Bhiodh sinn ri toirt Dhàchaigh leth-dusan cupan ’s leth-dusan truinnsear an-còmhnaidh, mil-poit ’s bobhla. Bha e cho saor ann an siud a bharrachd air Steòrnabhagh.”* “Bhiodh sinn a’ ceannach ornaments agus aodach, curtains, aodach leapa, cèic mhòr cuideachd agus botal fìon agus jar mòr jam.”*

*Às an leabhar Clann-nighean an Sgadain le Tormod Calum Dòmhnallach agus Leslie Davenport (Acair Earranta, 1987).

An gàire mar chraiteachan salainn

ga fhroiseadh bho ’m bial

an sàl ’s am picil air an teanga,

’s na meuran cruinne, goirid a dhèanadh giullachd,

no a thogadh leanabh gu socair, cuimir,

seasgair, fallain,

gun mhearachd,

’s na sùilean cho domhainn ri fèath.

bho Clann-nighean an sgadain le Ruaraidh MacThòmais

Their laughter like a sprinkling of salt

showered from their lips,

brine and pickle on their tongues,

and the stubby short fingers that could handle fish,

or lift a child gently, neatly,

safely, wholesomely, unerringly,

and the eyes that were as deep as a calm.

There are sayings ‘Cho coltach ris an dà sgadan’ and ‘Cho marbh ri sgadan’. Do you know what they mean? What do you call a smoked herring?

Some useful links…

Tobar an Dualchais

1. A humorous song about the benefits of eating salt herring and potatoes.

3. A’ mhaighdeann-mhara – The mermaid.

Go to www.tobarandualchais.co.uk yourself and search for ‘herring’ and you’ll find lots of interesting audio files.

Jamie Oliver Recipe (Go on, impress the Eaconamas Dachaigh teacher!)